The Carignan-Salières Regiment was a Piedmont French military unit formed by the combination of two other regiments in 1659. They were led by Governor, Daniel de Rémy de Courcelles, and Lieutenant General Alexandre de Prouville, Sieur de Tracy. Approximately 1,200 men (Piedmont, Savoyard and Ligurian) arrived in New France in the middle of 1665.

Seven ships were used to transport the regiment to New France. The Le Vieux Siméon, departed La Rochelle 19 April 1665, arriving at Quebec 1 July 1665. On board were the companies of La Fouille, Froment, Chambly and Rougment. The Le Vieux Siméon was a Dutch ship chartered by a La Rochelle merchant, Pierre Gaigneur.

La Paix and L’Aigle d’Or ships carried the companies of La Colonelle, celles de Contrecoeur, Maximy, and Sorel, and de Salières, La Fredière, Grandfontaine and La Motte. These both were royal ships of the king’s navy that departed from La Rochelle 13 May 1665, arriving at Quebec 18 August 1665.

Le Saint Sébastian and Le Justice. Aboard Le Saint Sébastian, were amongst the next seven companies being transported to New France. Newly appointed Intendant of New France, Jean Talon, and the Governor Daniel de Rémy de Courcelles. Aboard the final two ships were the companies of Du Prat, Naurois, Laubia, Saint-Ours, Petit, La Varenne, Vernon. These last two ships to depart from France left La Rochelle 24 May 1665, arriving at Quebec 12 September 1665.

Four companies arrived with Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy on the Brézé from the Antilles, arriving in New France 30 June 1665. The captains of these companies were La Durantaye (Chambellé), Berthier (L’Allier), La Brisardière (Orléans), Monteil (Poitou). Tracy had been in the West Indies as part of his royal commission to officially establish Louis XIV’s rule of the French colonies, following the King’s takeover of the French territories after the bankruptcy of the Company of 100 Associates.

The last ship to sail from France associated with the regiment was the Jardin de Hollande which carried the provisions and equipment for the troops.*(Depending on sources, there are some contradictions as to when ships arrived in New France and what companies were on board said ships.)

The regiment’s service in New France began when a third of them were ordered to build new forts along the Richelieu River, the principal route of the Iroquois marauders. Fort Chambly formerly known as Fort St. Louis at Chambly, Fort Sainte Thérèse, and Fort Saint-Jean at Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, were along the Richelieu River and were constructed as ways to limit Iroquois nation attacks on citizens of New France. Fort Sainte Anne in Lake Champlain was near the river’s source. All of the forts were used as supply stations for the troops as they were deployed on their two campaigns into Iroquois nation land in 1666. Fort Chambly as constructed in 1665 was the first wooden fort constructed in New France and had a rudimentary wood wall system with a building in the center of the fort. Inside, and near the center building, were small buildings for the troops.

The first of the regiment’s campaign took place in the winter of 1666. The expedition was initiated by the governor, Daniel de Rémy de Courcelles. General Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy agreed to the campaign after the Mohawks refused to attend a delegation of the Iroquois nations and French leaders in Montreal in November of 1665. At this delegation the French entered into agreements with the Oneida and Onondaga nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, who were there to represent themselves as well as the Cayugas and the Senecas.

The campaign was made up of about five hundred men of regimental soldiers, a number of Indians, and an estimated 200 volunteer habitants. The column ended up getting lost, wandering in the wilderness for three weeks before ending up on the outskirts of the Anglo-Dutch settlement of Schenectady. The soldiers came across a village that they assumed was Mohawk and launched a brutal attack, ravaging the village and killing two and severely wounding another two. The sounds of the battle were overheard by a passing Mohawk party of composed of approximately sixty warriors. The French and Mohawks engaged in a small skirmish which resulted in a small number of casualties on both sides. The French troops were at a tactical disadvantage as they were used to the pitched battles regulated by rigid drills commonly used in Continental Europe. Despite the experience of the soldiers of the Carignan-Salières Regiment, their tactics were useless against the hit-and-run tactics used by the Mohawks. The fighting ended when the burgomaster of Schenectady informed Courcelles that he was in the territory of the Duke of York. The burgomaster implied that if the French chose to stay in the settlement they would be vulnerable to attacks by both Indians and the English units stationed at Schenectady and Albany (less than 25 kilometres away). The French stopped the attack and the burgomaster agreed to provide the men with some provisions for their return journey.

The campaign was ultimately a failure. Nothing was accomplished and the regiment sustained great losses; 400 out of 500 died. Due to the hastiness with which the campaign had been launched and the harshness of the weather, most of the deaths occurred while travelling from and to Fort St. Louis. When Courcelles commanded that the troops were to meet at Fort St. Louis at the end of January, he said that they should be prepared with three weeks worth of provisions. In total, the expedition took a little over five weeks to complete. What is more, the men were ill-equipped—many left the fort without snowshoes—which contributed significantly to the campaign’s death toll.

The regiment’s second and final campaign was led by Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy. The plan was to enter into Mohawk territory, located northwest of Schenectady along what is now the Mohawk River. The necessity of the campaign was created by the declaration of the Second Anglo-Dutch War in the summer of 1666. King Louis XIV wanted de Tracy to lead the men into the same area where they were the last year near Albany and Schenectady. However, it was first necessary for the French to subdue the Mohawks to protect themselves from facing multiple fronts against both the English and Mohawks. In addition, they wanted to ensure that their two opponents would not ally themselves against the French.

The plan was for the regiment to regroup at Fort Sainte Anne on the day before and then push into Mohawk territory on 29 September 1666. The Late arriving of several parties meant the regiment left in three separate columns over a period of three days. The number of men available in the campaign was approximately 120 regimental soldiers, habitants and Native warriors. Because de Tracy sought to use the element of surprise and swiftly move into enemy territory, he ordered his soldiers to travel light. Thus, from the beginning of the campaign, the Regiment’s situation was precarious as the soldiers brought insufficient provisions and did not carry the necessary equipment for a lengthy assault. Inclement weather added to the danger of the mission and further threatened the campaign’s success.

As it moved inland, the regiment encountered four Mohawk villages all of which had been abandoned. The fact that the Mohawks abandoned their villages was fortuitous for the regiment since it was not operating at full strength and the soldiers were stretched over a large area. At this point in the campaign, the regiment probably would not have been able to withstand a large-scale attack. What is more, the villages were hastily abandoned thus providing the French troops with a supply of food, tools, weapons, and other provisions. After regrouping at the last of the four villages, Tracy ordered the soldiers to turn around and burn each one as they went, carrying all the loot they could back to Quebec. The Mohawks, though skilled in guerilla fighting, were caught by surprise by the speed of the French attack and were unable to engage the French. On 17 October 1666, the lands and fields surrounding the Mohawk villages were all claimed as French territory and crosses were erected to symbolize that claim. However, the French never returned to the area to enforce this territorial claim.

Despite the fact that the French troops had not directly engaged the Mohawks or the English, the campaign was considered a great success; the French finally assumed a position of tactical superiority over the Mohawk and Iroquois Confederacy which in turn gave the French a diplomatic advantage in the following peace talks. In July 1667, peace was signed with the Iroquois following a five-day summit. The main objective of the French during the negotiations was to consolidate their control of the fur trade at the expense of the Anglo-Dutch interests in Albany. They sought to do so by placing themselves in a position that allowed them to oversee the traffic of the fur trade in the region. As a result, the French were able to place French-speaking traders as well as Jesuits in a number of Iroquois village. To ensure the success of this agreement as well as the security of the traders and missionaries, a system of hostages was implemented. Each Iroquois village was required to send two members of a leading family to live among in the St. Lawrence Valley. Following the ratification of the treaties of 1667, the peace was kept in the region for twenty years. The peace treaties of 1667 also signaled the end of the regiment’s operations in New France. Nonetheless, the troops of the Carignan-Salières Regiment were held in duty until another means of protecting New France could be devised.

The first regulars of the Carignan-Salières were dressed for “efficiency rather than looks”, but they were still rather poorly equipped during their first year. During the first year, the king sent only 200 flintlocks and 100 pistols for over 1,200 men. Below are descriptions of some of the equipment used:

Powder horn: used to store gunpowder for firing their weapons. Black powder: used to arm and fire the newly issued muskets of the regiment. Sword: used commonly for hand-to-hand fighting and every soldier had one.

Flintlock musket: became the main weapon of long range fighting for the Carignan-Salières. It replaced the matchlock musket that was common in early years due to its increased reliability and ability to be fired without the use of an external flame. Additionally, it was capable of a much higher rate of fire than the earlier matchlock.

Bayonet: the Carignan-Salières were one of the first regiments to transition to the bayonet, which was introduced in 1647. Pistol: a standard issue weapon but was not in high-supplies in New France. Slouch hat: was worn in place of later tricorn hats. It was better at repelling rain and wind from the faces of soldiers. Uniform: The Carignan-Salières wore brown coats with contrasting colour sleeves. The Carignan-Salières were one of the first French forces to wear uniforms.

With the end to the Iroquois threat, King Louis XIV decided to offer the men of the regiment an opportunity to stay in New France to help increase the population. As incentive, regular officers were offered 100 livres or 50 livres and a year worth of rations. Lieutenants, alternatively, were offered 150 livres or 100 livres and a year worth of rations. Officers were also offered the incentive of large land grants in the forms of seigneuries. This offer was particularly beneficial to such men as Pierre de Saurel, Alexandre Berthier,Antoine Pécaudy de Contrecœur, and François Jarret de Verchères, who were granted large seigneuries in New France.

Although the majority of the regiment returned to France in 1668, about 450 remained behind to settle in Canada. These men were highly encouraged to marry, being offered land as incentive. As a result, most of them did marry newly arriving women to the colony known as Filles du Roi. The largest import of women to New France occurred during the 1660s and early 1670s, largely in response to the need to provide wives for the regiment.

Besides just rewarding Carignan-Salières officers by granting them seigneurial tenures, the tenure properties served an ulterior purpose. The properties granted to Contrecœurand Saurel were placed in strategic areas that could be used as a buffer between invaders both foreign (the British) as well as domestic (the Iroquois). It was believed that the men of the Carignan-Salières would be the colonists best suited to defend the territories of New France, therefore many of them were given properties on the Richelieu river and other areas prone to attack. These Seigneurs would sub grant land to the men of their companies in order to create an even more thoroughly reinforced zone. Saurel’s land would later be known as Sorel-Tracy in Quebec, while Contrecœur’s property would later become a region named after himself.

The French had a practice of allotting noms de guerre – nicknames – to their soldiers (this is still continued, but for different reasons, in the Foreign Legion). Many of these nicknames remain today as they gradually became the official surnames of the many soldiers who elected to remain in Canada when their service expired as well as the names of cities and towns throughout New France.

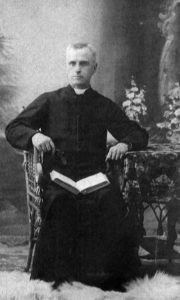

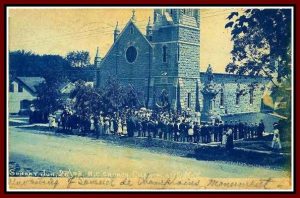

h. However, the congregation was rich in spirit and determination. Father Chagnon soon led the way in raising money for the construction of a new church which still stands in the village of Champlain, NY today. Though it was a struggle to raise the money for the church’s construction, the project was completed before the turn of the century. The new church not only gave the congregation a formidable place to worship, but it also earned Father Chagnon great admiration and respect.

h. However, the congregation was rich in spirit and determination. Father Chagnon soon led the way in raising money for the construction of a new church which still stands in the village of Champlain, NY today. Though it was a struggle to raise the money for the church’s construction, the project was completed before the turn of the century. The new church not only gave the congregation a formidable place to worship, but it also earned Father Chagnon great admiration and respect. In 1906, through Father Chagnon’s efforts, a Catholic school was opened. The Daughters of the Charity of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, who were a group of nuns that came to America from France came to teach the students.

In 1906, through Father Chagnon’s efforts, a Catholic school was opened. The Daughters of the Charity of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, who were a group of nuns that came to America from France came to teach the students.

The genealogy research took a huge leap forward when the world wide web came into our lives. It has given us the opportunity to connect to resources, places, and people and discover more about our family trees than ever. Now we have even more information since DNA (Deoxyribonulceic acid) came along. DNA is a molecule that contains the instructions an organism needs to develop, live and reproduce. These instructions are found inside every cell, and are passed down from parent to their children. So how is this information important to linking us to Indian descendants? Can science be more accurate than written documentation? Well, in this particular genealogy research case there are two thoughts (opinions) on this and a lot of information to back both sides. So lets look at some of this information and then you decide “Are we linked to an Indian descendant?”

The genealogy research took a huge leap forward when the world wide web came into our lives. It has given us the opportunity to connect to resources, places, and people and discover more about our family trees than ever. Now we have even more information since DNA (Deoxyribonulceic acid) came along. DNA is a molecule that contains the instructions an organism needs to develop, live and reproduce. These instructions are found inside every cell, and are passed down from parent to their children. So how is this information important to linking us to Indian descendants? Can science be more accurate than written documentation? Well, in this particular genealogy research case there are two thoughts (opinions) on this and a lot of information to back both sides. So lets look at some of this information and then you decide “Are we linked to an Indian descendant?” Who is this? This is Louis Bouchard. He was born September 18, 1850 in St. Paul’s Bay, Quebec. The son of Thomas Bouchard and Luce Sauliner. He immigrated to the US in 1870. Louis was in business for himself, selling wood and coal from the back yard of his home at 200 N. Champlain Street in Burlington, VT.

Who is this? This is Louis Bouchard. He was born September 18, 1850 in St. Paul’s Bay, Quebec. The son of Thomas Bouchard and Luce Sauliner. He immigrated to the US in 1870. Louis was in business for himself, selling wood and coal from the back yard of his home at 200 N. Champlain Street in Burlington, VT.